My Experience Living and Working in China, Part I

In this four-part article, I’ll go over some of the lessons I learned living and doing business in China’s tech industry. During my time in China, I’ve led a team of 10+ engineers to develop a location-based IoT and sensing platform, co-founded an open-source project called Towhee, and developed countless relationships with folks in a number of difference cities (many of whom I now consider good friends). I’ll go over some of the common misconceptions about China ranging from living and working in China to the government’s pandemic response.

Part I of this blog post covers some of the basics without diving too deep into the tech world: some interesting things I learned while living, working, and interacting in China. If you have any questions, comments, or concerns, feel free to connect with me on Twitter or Linkedin. Thanks for reading!

Update (03/29/2022): Part II is up. You can read it here.

Before I begin, a bit about me. I was born in Nanjing, China, but moved to the US when I was barely three years old. I spent about five years in New Jersey before moving to Corvallis, Oregon (a place that I am, to this day, proud to call home). I moved to Norcal for college, studying EE (with a minor in CS) at Stanford. I stayed there for my Master’s degree as well, which I completed in 2014. Afterwards, I worked at Yahoo’s San Francisco office as a Machine Learning Engineer for two years. As a hybrid software development & research role, I was able to research and productionize the industry’s first deep learning-based model for scoring images based on aesthetics. I also had the pleasure of attending Yahoo’s internal TechPulse conference (where my co-author and I won a best paper award) all while keeping up with interesting deep learning uses cases. All-in-all, I was quite happy with the work I was doing, but also slowly started to develop the entrepreneurship itch.

In the lead up to 2017, I returned to my Electrical Engineering roots and co-founded a company developing solutions for indoor localization and navigation. Efforts I put in towards finding investment continuously had little to no return - feedback we got from a lot of investors was that they believed in the team, but that the product lacked a “viability test” with an initial customer, something difficult for an early-stage hardware startup due to the high development overhead. I had some simulations and early board designs which I believed was enough, but for an investor, diving deep into an unknown company’s technology can often be costly in terms of time and energy.

This is where my story takes a bit of a turn. In late 2017, the company received an early-stage seed investment offer from mainland China, and after a bit of consideration, we decided to go for it. It was at this point that a lot of friends and family asked me a question I’ve become very good at answering over the years: Why did you choose to leave Silicon Valley for an unknown country with less talent and an arguably inferior tech industry? The answer is threefold: 1) I felt that Chinese investors were more open to funding hardware startups due to the ultra-fast turnaround times for fabrication, 2) the bay area was just getting too damn expensive for my taste, and 3) from a personal perspective, I wanted to understand my birth country from cultural, social, and economic standpoints. I felt good about my decision and thought that the greatest challenge would be language; my Mandarin was workable but far from proficient.

San Francisco Chinatown is a poor caricature of Qing dynasty China. Same goes for the architecture you see in Chinese restaurants across America. Photo by Dennis Jarvis, CC BY-SA 2.0 license, original photo.

Alipay, WeChat, and QR codes

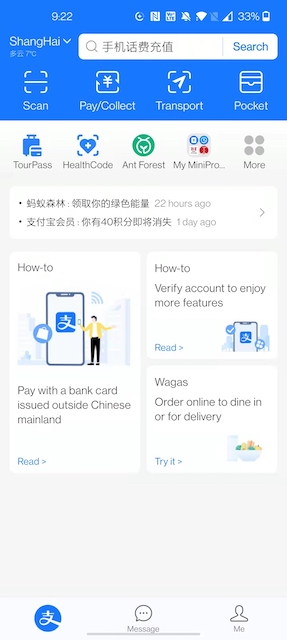

The very first thing you’ll learn about China is that everything revolves around either Alipay (支付宝) or WeChat (微信), two apps known primarily for their payment capabilities. What a lot of folks outside China don’t know is that these two apps can be used as gateways to a number of other mini-programs (小程序), i.e. subapps developed by other organizations such as KFC, Walmart, etc. These subapps can be used directly within either Alipay or Wechat, forgoing the need to individually download apps from an app store. Imagine ordering furniture from IKEA, dinner from Chipotle, and movie tickets to Century Theaters all from the same app - that’s Alipay/Wechat for you.

The obvious downside to this is that personal information becomes extremely centralized. If something like this were to happen in the US, antitrust lawsuits would come faster than a speeding bullet, and for good reason too - big conglomerates monopolizing data is dangerous and their wide adoption stilfes innovation. While Alipay and WeChat were years ahead of the US’s card-based (credit/debit) payments system when first released, Android Pay and Apple Pay (NFC-based) have since then become a lot easier to use.

Alipay and WeChat work by opening a camera and scanning a QR code, which redirects you to the store's payments page. You can then pay an arbitrary amount of RMB, which will immediately show up in the payee's balance once complete. Photo by Harald Groven, CC BY-SA 2.0 license, original photo.

Here's a screenshot of my Alipay. Its primary use is for payments, as evident by the top row, but mini-programs (second row from the top) have now become an important part of the app.

Alipay and WeChat’s success within mainland China are in large part due to the smartphone + QR code revolution, which has truly permated all aspects of Chinese life. Shared bikes can be unlocked by scanning a QR code on your phone. You can add friends on Alipay and WeChat using QR codes. Many Communist Party of China (CPC) functions rely on tight Alipay or WeChat integration. You can even login to third-party websites and check in as a guest in office buildings via QR codes. I am by no means a security expert, but this system somehow feels a bit gameable despite its widespread use by over a billion people.

Red tape, CPC style

While Alipay and WeChat have made life considerably easier for the majority of people living in China, many civil and commercial processes are still incredibly difficult and filled with unnecessary paperwork. Registering for a company and acquiring a work permit in China is quite possibly one of the most insanely frustrating things on Earth. I won’t go into all of the details, but just know that it involved a mountain of paperwork, letters of commitment, countless passport scans and other documentation, etc… We ended up hiring an administrative assistant to handle a lot of this work for us, but the amount of time and energy one has to dedicate towards this can be a bit demoralizing.

Some provincial (the equivalent of a state in America) governments have issued new policies aimed towards combating the problem of excessive paperwork. But the CPC is massive, and massive entities have even larger amounts of inertia. Rather than reducing the amount of mandatory paperwork, many of those policies revolved around reducing the number of trips needed to see the process to completion. This is definitely a step in the right direction, but compiling a thick folder of paperwork is still not a fun experience.

A common joke in China is that there are four castes. From top to bottom these are: 1) CPC officials, 2) foreigners, 3) white collar workers, and finally 4) blue collar workers. Even with this supposed semi-VIP treatment, getting a business license such as this one is something I do not want to go through again.

The same goes for pretty much all processes which require some sort of government approval, including but not limited to acquiring a work permit, registering an address change, and replacing a lost ID card. Even flying to China requires a mountain of paperwork and approvals, even if you already have a Chinese visa. My main problem with all this is the CPC’s complete lack of transparency. Why can’t I transit through a third country on my way to China if I’m going to have to undergo 14 days of mandatory hotel quarantine plus another 7 days of home quarantine anyway? From a foreigner’s perspective, this is one of the most frustrating aspects of China in an otherwise amazing experience - CPC overreach in almost every aspect of everyday life. The CPC grossly mismanages via overregulation in some sectors and underregulation (hello, housing market) in others.

Social regression, economic growth

This ties into another common misconception about China - the idea that the government wants to track everything you do at all hours of the day (for the moment, let’s ignore the feasibility of doing so for a population for 1.4 billion people) through a combination of CCTV, mobile phones, and browsing habits. I’ve read countless articles written by American and European media outlets overstating the dystopia that China has fallen into, but the reality is that the Chinese government cares little for storing said data long-term and uses it primarily in criminal cases. I was involved in a project that uses face recognition to track residents going in and out of communities; not only were the residents eager to have such a system installed, but it eventually also helped track a man guilty of sexual assault. Data from such a system was also entirely managed at the local level and not automatically shared with the provincial or central governments.

Xinjiang and Tibet are two exceptions to this which I won’t dive deep into. I also haven’t been to either province, so it would be inappropriate for me to comment on what’s going on in Western China.

Other surveillance programs such as social credit (社会信用) and city brain (城市大脑) are also widely misunderstood. The social credit system primarily punishes and constrains businesses rather than people, while social credit for individuals is somewhat analagous to a background check in America. A lot of American and European commentators will point out some insane social credit rules, such as deducting points for cheating on the college entrance exam (essentially the SAT on steroids); while I do not disagree, there are undoubtedly similar occurances for American laws. When I was still a student at Stanford, I once lost an internship opportunity because a “traffic violation” - biking at night without a bike light - showed up on my background check. In all fairness, I consider it to be extremely easy to stay off China’s social credit “blacklist” - just be reasonable and avoid breaking the law.

China’s “city brains” are a totally different beast, designed to anticipate and reduce traffic, improve city planning, and provide advanced 3D models and visualization techniques. My understanding is that most city brain projects achieve… none of these, despite the fact that cities pay the equivalent of tens to hundreds of millions of dollars for just one of these solutions. An interesting side note - a recruiter once tried getting me to lead Yiwu’s city brain project, but it fell through after he discovered I wasn’t a Chinese citizen (these projects, for obvious reasons, strictly prohibit participation from non-Chinese citizens).

An image I found of Pudong District's (Pudong is a district in Shanghai, home to Shanghai Pudong International Airport i.e. PVG) city brain platform via a Baidu search. Although it looks fancy, there is really little to no new underlying technology behind these systems.

You might wonder how China’s economy is able to grow at such a blistering pace despite the huge number of arguably inefficient government programs. The answer is rooted in East Asian culture: work ethic. Blue collar Chinese workers are willing work 60+ hour weeks while sustaining themselves on ramen and $1.5 cigarette packs every day just to ensure their kids can get the best education and an improved quality of life. The whole concept of 996 is rooted in the Confucian ideals of hard work and industriousness. The “laziest” men and women in China are arguably owners of small- to mid-size businesses; they are often the last to arrive and first to leave from work. The CPC loves to take credit for China’s recent growth, but the reality is that the growth was the result of Chinese work ethic plus a switch from central planning to a mixed economy.

By industriousness, I really do mean everybody. In 2019, I visited a prison in Jiangxi to discuss a potential prisoner safety solution. In a meeting with the vice-warden, he tacitly mentioned how Adidas shoes were being made in the prison that he was running. We quickly pulled out of that project. I haven’t bought Adidas- or Nike-branded shoes since1.

Personal identity

With the current political climate and state of affairs in mainland China, many Gen Z-ers and Millenials (mostly from Guangdong Province), as I consider Macau, Taiwan, and Hong Kong to be separate territories) who hail from mainland China but don’t refer to themselves as Chinese, instead calling themselves Cantonese. While some simply wish to preserve personal identity, there are also many who dissociate themselves simply because they believe the rest of China to be inferior. I’ve heard some of the most asinine reasons - people spit too often in the streets, everybody plays loud Douyin/TikTok videos while riding high-speed rail, too many cigarette smokers, etc. These are the same people who conveniently forget that some sidewalks along the Mission are lined with old discarded chewing gum, that loud music is played frequently on BART or in a BART station, or that open drug usage occurs nightly in the Tenderloin.

I strongly dislike the CPC, but have immense love for Chinese people and Chinese culture. China is an super-massive collection of people that, in my eyes, have made incredible economic and social progress since my birth year, and will continue to do so in the decades ahead. And as a result of all of this, I’m proud to call myself Chinese American.

Wrapping up

Entire dissertations could be dedicated to each of the above sections, but I wanted to highlight misconceptions and some other bits of information that might not be as readily accessible. In particular, the previous section is by no means a comprehensive list of social issues that China is facing, but rather a brief summary of things that might not be too well understood in the West. #MeToo2, a declining natural birth rate, and racial divisions are just a small number of similar/parallel issues that are happening in both America and China.

If you made it this far, thanks for reading. This post has been a bit rambly and all over the place, but the next couple should hopefully be a bit more focused. If you liked this article and are an open-source developer like myself, please give the Towhee project a star on Github as a show of support.

In part II, I’ll cover the Chinese tech scene, from 996’ing to the open source community. Stay tuned!

-

Forced labor in Xinjiang has made headlines in recent months, but in reality, it happens everywhere in China. ↩

-

Justice for Zhou Xiaoxuan. ↩